“I don’t see myself as an artist, I see myself as a director,” says Ben Ditto. Photo provided by Ditto.

“I don’t see myself as an artist, I see myself as a director,” says Ben Ditto over Zoom. The director, fresh off a trip from Iceland, meets me on a six hour time difference between Texas and the U.K.

In 2022, aesthetics are more sovereign than ever – just look through the thematically framed round up of your pinterest board or a recent photo diary from Paris fashion week. A curiosity that pops up in this era is the progression of art feeding into technological advancements. How can a “utopia” be explored and presented contemporarily? During this period, the director has been one of the most influential initiators of this progression, proving that the “future” is already exposed.

Through curation, literature, film, and even live experience, Ditto has solidified his place as a distinguished director. From curating digital art exhibitions to crossing over science and art for luxury brands, his work often wraps you up in ideas of modernity, publicizing strange, unconventional things and turning them into avant-garde matter. “I wouldn’t say I go back into history, it’s not something I consciously do, but definitely culture and context.”

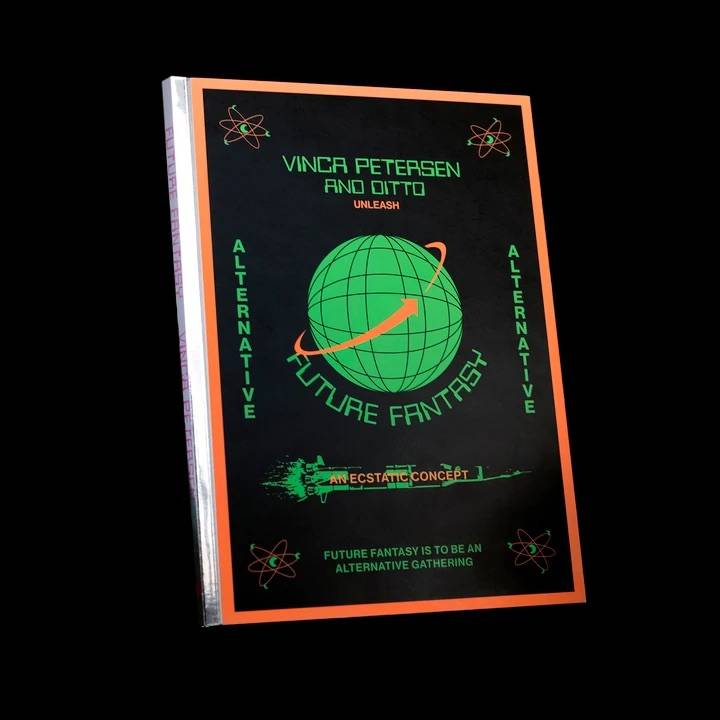

After studying at the University of Art London from 2003-2006 and completing a Master’s program at the Royal College of Art from 2006-2008, he co-founded Ditto Press with Lynsey Atkin. As the first company in the UK that specialized in Risograph printing, Ditto Press published several notable works including “Grobišče: Society, Politics, & Mass Graves,” a book that explores the massacres and war graves in Yugoslavia and “Future Fantasy,” an archival photo book documenting the illegal rave scene of the 1990s.

I’ve had the chance to see his work twice in person. The most recent was last November, outside the Louis Vuitton store on the Magnificent Mile: “The Louis200 Trunk.” Ditto, among 199 other commissioned artists, companies, and directors, were encouraged to express their vision in celebration of Vuitton’s 200th birthday.

Ditto’s piece literally glowed in the dark. Revisiting a pandemic that took place in Louis Vuitton’s youth – cholera – Ditto worked with scientists Marisa Zuk and Kenneth Robinson, creating a custom glowing bacterium for the trunk. “The piece is a statement on the influence of infectious disease on culture, representing the possibility that biotechnology can transform a contagion into an aesthetic medium, or tool for future therapeutics,” said Ditto in an interview with the brand. His work stays consistently experiential, whether online or in person.

The first time I saw Ditto’s work was in May 2019, in the Texan-mopped crowd of The 1975’s “Music for Cars” tour. His visual, projected on a giant LED screen behind the band, was a flashing mix of analog and digital code, 3D models of streets, and bolded lyrics synced up to “I Like America & America Likes Me.”

Aside from live visuals, Ditto has worked frequently with The 1975 on music videos such as the flashy, black-mirrored “People,” and the self-obsessed, Sergeant Pepper-inspired animation for “The Birthday Party.” For Ditto, working with The 1975 is “a truly collaborative thing.” He describes, “The whole team, everybody is really respectful of creativity and good to work with, they have a big reach, everything’s great. The music’s great, they have a really loyal fanbase and play these huge shows. Everything about it is exactly what I love doing.”

With a keen eye for artistic taste, choosing the right people to work with is one of his favorite parts of the job. Sometimes, not knowing how a project will end, or even start, can be encountered with curious ingenuity. “It can be a gamble, but it can’t be a fuck up.” Ditto’s success has flourished and centered around large groups and collaborations with others. Creating environments where people can do their best work is “sort of the dream scenario,” he declared. “Some of the most interesting things are when you think ‘Okay, what happens if I put this person with this person? Or if I put this person with this technology? Or this person and this technology into this situation?’ Then the magic happens.”

Now that inspiration has become a digital moodboard, it is rare for an artist not to share what they find interesting, current, and archival. Where most artists and directors stray away from any kind of social media to maintain a specific image, Ditto’s interactions with current events, pop culture, and his followers play into his work. If you tap through the encyclopedic slideshow of his Instagram story, you may catch the following: a Q&A sticker, reposted TikToks, or his cat, Jimmy. Photos of other artists’ work, reposted memes, and headlines fill the grid of his actual feed, establishing an observatory of culture through photos and follower interaction. If there was ever a director as engaging as his portfolio, it’s him.

“There’s a big conversation now with crypto[currency] about physical-digital interaction. ‘Phigital,’ they call it. It’s like, ‘how do we marry the physical world, and the digital world?’ Actually, what people are missing is that there is no distinction. The physical world is the digital world is the physical world.” With the emergence of digital space as the nucleus of interaction and literature over the past decade, even more so in the past two years, a bigger question of physical matter and tangible print comes to the surface.

“I think archiving is a very important thing, that’s for sure, but we can’t print all two-trillion photos that exist in the world on the internet now. We have to move past that. It’s not physically possible. If we want to be able to look back at culture in a thousand years and see what we were doing, it can’t be just print-everything. A lot of my career has been about exploring that, sort of.”

Having been appointed as a creative consultant for DAZED Beauty, a digital magazine, Ditto describes the ethos of the project being “a personal description of what beauty should be.” From turning eerie, uncomfortable visuals into an aesthetic through CGI artists, augmented reality specialists, and GAN (Generative Adversarial Network – a neural network that draws beauty images/selfies based off training information), a clear emphasis of intersecting technology, identity, and the human experience was at the forefront.

“It’s just gone everywhere. All of the stuff we were doing on Dazed beauty three years ago is now mainstream.” Where these ideas were once universally perceived as weird or even “ugly,” this vision has pioneered recent aesthetics in the past few years. “That’s what any good magazine should do. It’s not exclusive to DAZED Beauty, but I think any good magazine or any good cultural project should feed into the rest of culture. DAZED Beauty definitely did.”

While his resumé is enough to astound commissioners and connoisseurs, Ditto is able to recognize his strengths and weaknesses. After working on several music videos and short films, with an aim for a feature length directorial debut in the future, he points out his needs to hone film skills further. “I’m not trained working with actors and narrative and plot and things like that, that’s not inherently what I work with. Being able to recognize that I need to grow in that area is important. Yeah, I would love to make a feature film, but probably two or three more short films first, for sure.”

In the last film he made, production was carefully overseen through aspect-specific Whatsapp chats. Having the opportunity to pinpoint what made all of the minor and major aspects of a film important, he is able to cohesively understand how even the finest details can make or break a project. “What is it about each of those disciplines that makes it good? Can you tell what a good manicure is? Can you tell what a good set is? Can you tell all of these things? That’s such a valuable thing to do if you want to be directing people.”

The “creative process” among directors has become a sacred focus. A clear, unabridged vision is essentially ideal, but it should also be a prospective chance to explore different outcomes. “I think the process can be a bit more chaotic or a bit more experimental, but the outcome I tend to have a very clear idea of what I want, and I’ll say that to people in the beginning of the process.”

Even for someone that has worked as long as Ditto has, the outcome of a project can still adapt as it is conceived. Has a project started in one direction and then ended up somewhere else? “I think it’s almost always more beautiful than I was expecting, or different to what I was expecting, which is great. I have the sort of personality where I will keep doing stuff until it’s good rather than be like ‘Oh here’s a thing that didn’t work out. Fuck it, I’ll move on.’” Ditto concedes that “can be a useful way to approach things, sometimes. I’m not writing that off. I think that people are judging me on every single thing I ever do and actually the evidence shows that you can be very, very talented, and occasionally do something a bit shit, and people will let that fly. But I don’t ever want to do anything shit.”